If you have administered vaccinations previously you may be aware that there are some vaccines that are thought to be more painful than others. You may have even possibly heard one of the following phrases from one of your vaccine recipients:

“wow, I didn’t feel that one at all”

“ouch, that one really hurt”

“that one left me with a really dead arm for days”

So what is it that causes the pain from a vaccination? and why is it that some vaccines are possibly perceived as being more painful, and others may hardly hurt at all?

“Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever and wherever the person says it does”

McCaffery, 1968

Pain it itself is a very subjective matter, everyone experiences pain in different ways and what causes pain for one person, may not for another. Measurements and expressions of pain in itself are also very hard to quantify which makes it a difficult subject to research.

It is thought that one of the contributing factors to whether someone finds a vaccine painful is actually down to the individual themselves. We have all probably given a vaccine to someone without them experiencing any pain and then given the same vaccine minutes later to someone else who found just the opposite, so why is this?

Why some people feel more pain than others or experience a stronger inflammatory response can also be down to individual variants. It is known that age can decrease immune responses. However, research on the how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity suggests BMI, genetics, gender and prior immunity to a disease can also have a possible contributing factor to the side effects experienced.

Whilst the physical act of a needle breaking through the skin into the layers of fatty tissue and muscle can in itself be a possible source of pain. It is suggested that the variations in pain between vaccines may be down to the different physiochemical properties of the vaccine itself. Let’s have a look at some of the reasons why a vaccine can cause pain.

Vaccines contain antigens from the virus, bacterium, or toxin in either a killed inactivated or a weakened live form.

These side effects may not always be felt straight away but can develop over a few hours once the immune system begins to work and can sometimes last for several days. They are very common with most vaccines and demonstrate the immune system is functioning.

It is thought that different vaccines can generate variable degrees of an inflammatory response, which can also possibly affect the degree of pain experienced.

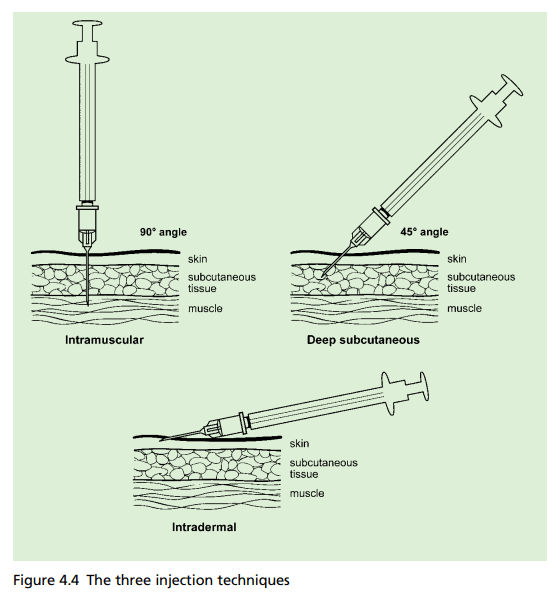

Another factor that can potentially influence which vaccines are more painful is the route by which they are administered.

There is some thought that it could be the components of the vaccination that may cause certain vaccinations to be more painful than others.

Consistency is another factor that may impact how painful a vaccine feels.

Some may believe that a higher volume of the vaccine might be a contributing factor to an increase in pain.

Other possible contributing factors that may impact pain felt from vaccines can include the speed of the injection, the needle itself and the anatomical site of the injection. It has also been thought that because vaccine’s are kept in the fridge, the colder temperature on administration can possibly cause more pain.

This is not a well researched area, there are very few studies comparing the level of pain from certain vaccines.

With limited research available, that often leaves us as vaccinators having to rely on our individual experiences of which vaccines may cause more pain. We may do this by gathering feedback from our patients or through visual signs of pain. We may also rely on what our peers and colleagues have told us or what we may have read or heard. This highlights the need for more research to be done on this topic to enable a greater understanding of vaccine related pain and how it can be reduced.

We may feel from personal experience that certain vaccines seem to be more painful than others. There is also lots of research to show that pain can increase with repeated painful stimulation, and therefore discomfort may rise with each injection.

Whilst this is again not a heavily researched area, a study comparing DPTaP-HiB and PCV vaccine’s, showed that infants demonstrated overall less pain when receiving the PCV vaccine last.

This practice is also recommended in the World Health Organisation (WHO) Position Paper on reducing pain at the time of vaccination. However the issue is that we don’t have data for all vaccines, so how do we know which order to give them in?

WHO states that in the absence of a particular grade of the painfulness of vaccines, vaccinators should utilise their practical expertise to decide the appropriate order of injections.

Encourage individuals to relax their arms. It’s very normal to immediately tense up when someone is about to inject you with a vaccine. However, relaxing the muscle can ensure that it isn’t tense which is thought to contribute to pain. One good tip if someone isn’t able to relax their muscle by themselves is to gently press down on the shoulder with one hand. This encourages their arm to drop which subsequently helps the muscle to relax. For someone who is needle-phobic or prone to fainting, you can encourage them to lie down which can also help to keep the muscles relaxed.

Positioning should be appropriate to the age. With infants and children, holding them in the cuddle position has been shown to reduce pain and provide comfort.

There is some evidence that skin-to-skin contact, breastfeeding and pacifiers can help reduce crying and stabilise heart rates in infants during medical procedures.

There is a lot to be said of mind over matter. Helping to focus on other things and take attention away from the procedure can help to reduce pain. Children can be distracted by toys, bubbles or games on a phone. Older children, adolescents and adults can be distracted through chatting, listening to music or breathing exercises.

There is some suggestion that watching the needle go in can enhance pain perception so it’s usually advised to look away!

After vaccination, encouraging movement of the arms can help to disperse the vaccine and prevent fluid from building up. However it is not recommended to massage or rub the injection site after vaccination. This is particularly important with intramuscular injections as there is a chance that it could possibly cause the vaccine to back up through the subcutaneous tissue and therefore alter its effectiveness.

Whilst pain relief isn’t recommended routinely to be given pre or post-vaccine (with the exception of MenB vaccine). If someone has soreness and pain at the injection site, then pain killers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen can be given if suitable. Ice or a cool compress can also be applied to help to reduce pain and swelling if required.

If you have read all the above and are still wondering if there is anything else you can do to help relieve pain from the vaccine – maybe give this one a go! New research looking at the effects of experimentally manipulated facial expressions on needle-injection responses suggests that getting your vaccine recipients to smile can help reduce pain. (NOTE: it needs to be a big smile! – one of the ones that lift the corner of the mouth and crinkle the sides of the eyes!).

Pain is a common known side effect of vaccines and demonstrates the immune system is functioning appropriately. However, whilst pain can be expected, individuals should be reminded to watch for any indications of infection or more severe adverse reactions including:

Although very rare, it is possible pain can be due to a shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA), when a vaccination is given too high. This highlights the need to ensure appropriate anatomical markers are used when preparing for vaccination. Individuals with symptoms of SIRVA should be advised to seek immediate medical advice.

We know one of the barriers for some individuals in not getting vaccines is due to the perception of pain that it may cause. Whilst we may not be able to eliminate pain completely, by having an understanding of vaccine pain it can help us as vaccinators improve patient experiences and employ measures to reduce overall pain experienced.

Giving you written and video content to answer all your questions on primary care education from Phlebotomy to Travel Health.

Subscribe now to be kept updated with our latest posts and insights.

Start typing to search courses, articles, videos, and more.